Plant FAQs: Why do Plants get Reclassified?

|

|

Tiempo de lectura 13 min

|

|

Tiempo de lectura 13 min

When you’re browsing for houseplants you may notice some nonsense-looking words attached to each plant. This is the plant’s scientific name, given in Botanical Latin. Confusingly, this language also incorporates Greek words and many names of places and people from all over the world of horticulture. The system of classification we currently use applies to all living organisms, and is called the Linnaean System of Classification after the scientist who established it, Carl Linnaeus.

Linnaean Classification gives a unique scientific name to every organism, helping to make scientific discovery and research consistent across languages and institutions. The naming of algae, fungi and plants is independent of that for animals, and it’s this section that we’ll be focussing on here. It’s a helpful system because while a plant may have 20 (or more!) common names, it will only have one scientific name. Under the classification system, the natural world is divided and subdivided into the sections:

Kingdom (here, we are in the plant kingdom, or Plantae)

Phylum (plants are divided into mosses (Bryophyta), ferns (Pteridophyta),and seed plants (Spermophyta))

Class (there are 24 plant classes, split mainly by how the stamens are arranged in flowers)

Order (this section groups related families together)

Family (this groups Genera of plants by similar features - it can be helpful to know which of our houseplants are in the same family as the care is often similar)

Genus (a grouping of species that are quite closely related to each other - again, this is useful for houseplant keepers as the care of any member of a genus is probably similar to others.)

Species (this is the smallest unit that every plant or organism will fit into - generally defined as a group of organisms can reproduce with each other and produce fertile offspring)

We only really need to care about these last two in day-to-day life - they are the ones we use and which are most likely to change as understanding improves.

A scientific name is made up of the Genus and Species names (AKA ‘specific epithet’). They are the most specific, so the most useful for identification. Naming the other five sections, every time, would just be excessive - and get a bit boring. The Genus name is always capitalized, and this specific epithet, which gives you the species, never capitalized. A scientific name should always be put in italics. If you’re talking about a lot of different species in the same genus, you can use a kind of shorthand, abbreviating the genus to its first letter, i.e.: Genus speciesis shortened to G. species.

Changes in the scientific name happen when more discoveries are made and the classifications of different organisms change. Hopefully you now understand how the system works - but why might the names change?

There are two main factors that come into name changes or our favourite houseplants…

Precedence: The first name to be published for a plant gets precedence, so if an earlier name is found or two plants are found to be the same where they were thought to be different, the earlier name becomes the accepted one. Rules like this are codified in the International Code of Nomenclature, a document actually drawn up to govern the naming of organisms in the plant kingdom.

Improvements in scientific understanding: DNA analysis is improving our understanding of plant classification, and most that are reclassified now are because of this. Plants are renamed when they are found to either be genetically identical to or distinct from another plant when the opposite was thought to be true. When they are found to belong somewhere slightly different in the categories we have divided the plant kingdom into, the accepted scientific name - the one used as standard by scientists and researchers - changes.

Basically - our scientific understanding is always improving! And it’s exciting to see this as plant classification changes and develops.

In our research on the plants we stock, we have found quite a few different stories on plant reclassification. Read on to find some of my personal favourite examples - and find out if any of your own houseplants have had a scientific name change.

Please bear with me while I piece the stories together . Even with high levels of digitisation, it is hard to track plants by their names through history - especially when they change halfway through the scientific discussion!

Some plants are initially classified as one Genus before being moved to another . Sometimes this happens to a whole group of plants. In the following examples, some of the plants began as the same genus as a whole other group before being moved to their own one, while others began as a totally separate genus before being moved to the same and merged, when it turned out they were more similar than scientists initially had believed.

In 1832, the genus Homalomena was first published. Within the plants originally thought to be part of this genus, a group were later found to be more distinct than had initially been thought. These were moved to the Genus Adelonema after it was established in 1860. This is a long process, though - the Queen of Hearts plant, Adelonema wallisii,was only moved from Homalomena to Adelonema in 2016!

A genus you may be more familiar with is the Calathea genus. But did you know that most houseplant Calatheas are actually in a different genus now? This recent development has seen many species make the jump from Calathea to Goeppertia as analysis has revealed them to be more genetically similar to that genus.

Have you heard of the rare houseplant Apoballis acuminatissima? Perhaps not - I hadn’t before we stocked it last year. And it has only had that name since 2010, when a paper reclassified it from the Schismatoglottis genus - better known as the Drop-Tongue Plants. The visual similarity had them grouped together for nearly 150 years, but 21st Century science has changed this classification too.

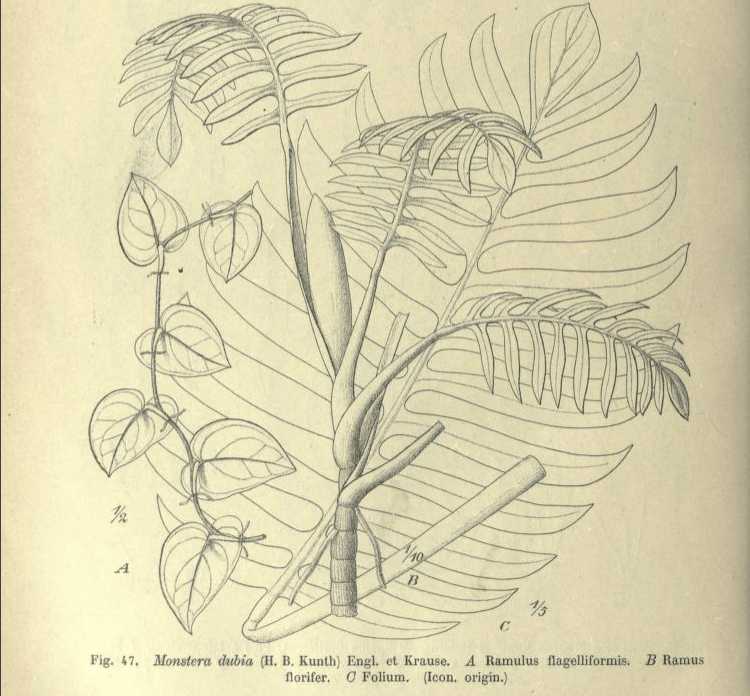

In 1825, an epiphytic plant found in Venezuela was named Marcgravia dubia, catalogued in a list of discoveries from an exhibition to what was then New Andalusia. The epithet dubia meant that the publishing scientist, Kunth, was unsure whether this was the correct genus. In 1908, a paper positing another genus name was published, and this classification has since remained accepted: Monstera dubia. One reason that this plant is so difficult to classify is the dimorphism it shows: juvenile leaves look totally different to adult leaves.

Finally, you may know the Snake Plant well - also known as Mother-in-Law’s Tongue, it’s a popular houseplant because of how easygoing it is. You may even have heard it called Sansevieria. But did you know that recent analysis has changed this classification? Sansevieria had been used since the name was published in Naples in 1787, but now it has been grouped into the same Genus as the Dragon Tree, Dracaena - there was not as much genetic difference there as previously thought. This is quite a recent development, and you will still mostly see Snake Plants for sale as Sansevieria, because that’s the name more people will recognise. In addition, this is a good demonstration that sometimes it’s just the Genus that changes, but sometimes the whole name changes. Sansevieria trifasciata, named in 1903, became Dracaena trifasciatain 2017. But you’ll find Sansevieria zeylanica in two places. The plant that was given this name in 1799 kept the species name, becoming Dracaena zeylenica,but the one which was identified as this in 1805 was found to be different. In 1829, it was identified as Sansevieria roxburghiana,and now the genus has been changed, as of 2018, this is the species name it has kept: Dracaena roxburghiana.

Something else you might see is more simple: a simple mix-up. We have had plants sold to us before as Syngonium nephthytis -but this plant doesn’t exist! This name is a mix-up, because the NephthytisGenus often gets mixed up with Syngonium, meaning sometimes both names end up on the plant. In this instance, the plant we actually had was a Cultivar of good old Syngonium podophyllum.

Priority of Publication is taken into account when naming plants. What’s that when it’s at home? I hear you ask. It means who got there first. The first person to publish a plant name gets dibs on naming it.

So when, for example, the species Agave lophanta was found to be a synonym of Agave univittata - the two being genetically identical - the name wasn’t on a flip of the coin. A. lophantha was published in 1850 - but A. univittata had beaten it by 19 years, having first appeared in 1831. So the name of both plants, now known to be one species, is officially A. univittata.

The species Hoya latifolia contains a couple of plants which were thought to be distinct species - H. macrophyllaand H. polystachyawere both later found to be identical to Hoya latifolia. They were knocked out for different reasons: H. polystachya was published later, so latifolia had priority of publication. But H. macrophylla was published in 1834, three years before H. latifolia in 1837. It was branded, though, as an ‘illegitimate name’ (the notation for this is nom. illeg.) This means it broke the rules of the International Code of Nomenclature at the time and was not considered valid. This is another way that plant names can be put aside and replaced.

You might see ‘var.’ or ‘ssp.’ in the middle of a scientific name. These mean ‘variety’ and ‘subspecies’ respectively, both ways that species are subdivided due to slight natural differences. And sometimes a scientific name changes because a variety or subspecies is found to be either more or less distinct than initially thought:

You may have heard of the Aloe vera - but did you know that this succulent was originally thought to be a variety of a different species? It was originally classified as Aloe perfoliatavar. vera in 1753, but by 1768 another paper had identified it as a separate species - and to this day, it is known around the world as Aloe vera.

And then there is Anthurium ellipticum, a plant which was initially thought to be its own species, and which is often sold as such. However, the Jungle Bush is actually a variety of another species - Anthurium crassinervium var. crassinervium to be exact.

Hybrids are formed when two different species breed , making a whole new plant. The pollen from one parent plant finds the stigma of the other, and the seed they produce is a combination of the two species. Most botanical hybrids are bred in cultivation, but it is possible for this to happen naturally too.

One of my favourite human-engineered hybrid plats is the Mother Fern. It’s got that lovely ferny appearance but isn’t quite as fussy as many other ferns. And that’s because it was bred to be stronger as a houseplant! It’s a hybrid between two Antipodean species of Asplenium, A. dimorphum and A. difforme. For this scientific name, we get a hybrid formula showing its parentage: Asplenium dimorphum x difforme(Plus the Cultivar name 'Parvati')

Sometimes there’s a long and complicated story taking plants to their current accepted classification. Here are a few convoluted examples…

The stunning nerve plant is now known as Fittonia albivenis. But it wasn’t always so simple. Originally, the white-veined and red-veined plants were classified as different species. In the 1860s, they were Gymnostachyum argyroneurum(for white veining) and G. verschaffeltii (for pink or red veining). In that same decade, they were reclassified to the Genus Fittonia , named for the Fitton sisters, but keeping the same specific epithets. This remained the accepted name for over a century, but researched published in 1979 saw the two species reclassified as one, and ever since, they have been Fittonia albivenis - with two cultivar groups, ‘Argyroneurum’ and ‘Verschaffeltii’ for the white or pink/red vein colours.

The Zygo Orchid is stunning in shades of purple and green. But it’s taken a while to get to its current naming status. Let’s take the Zygopetalum maculatum.Throughout the 19th Century it was moved from Genus to Genus, first as a Dendrobium (1816), then as a Broughtonia (1826) and finally settling on Maxillaria maculata(1832). But not for long! In 1970, the species was revisited and reclassified as Zygopetalum maculatum- the name it still holds today. You might wonder at how many Orchids there are - that’s because Orchid is a whole family of plants (the Orchidaceae), so there are many genera within it.

My third example here is one of *the* houseplant staples - the Golden Pothos, Epipremnum aureum. If you’ve ever wondered why we refer to so many plants by the name ‘Pothos’, it’s because this was the genus name given to many of them when they were initially discovered. The name comes from the common name for the plant in Sinhalese, a Sri Lankan language, and was applied to many a tree-climbing vine. However, once better scientific, and eventually genetic, analysis got in there, it turned out not all of them were that closely related , despite their similar shapes. What we know today as E. aureum started off as a Pothos (Pothos aureus), in 1880, and was subsequently described as Epipremnum mooreense in 1899, Scindapsus aureus in 1908 and Rhaphidophora aureain 1963. The current classification follows a 1964 paper - and thankfully, that has so far been the last word.

Sometimes a name doesn’t change , but a later name catches on. The Silver Sparkle Plant is often sold under the name Pilea glaucophylla as a houseplant. This name comes from a 1936 paper. However, the accepted name did not change as a result of this paper - the plant is still known as Pilea multiflora,as it was named in 1852. This name was given to a different type specimen , so it’s possible that it was thought to be a different plant for a while until the similarity was noticed and confirmed, but not before the name had really caught on in plant cultivation.

Often plants are sold without a specific epithet , and only the genus is given. This was the case when we first stocked Tradescantia ‘Green Hill’, but after researching we found that it had been identified in 2018 as Tradescantia mundula - so now we sell it under that name.

The other reason you may not get a specific epithet is if the plant is a hybrid of unknown parentage, or if there are just too many parent plants to list. This is the case sometimes with plants that have been in cultivation for a long time - we often find it difficult to confirm Begonia species , for example, even though there is a database available for some of the cultivars. And so often the Leopard Lily (Dieffenbachia)arrives with no species name, and none can be found. Most likely these are hybrids, but I am yet to find a list of these to confirm!

Hopefully you’ve found reading about the ins and outs of plant classification almost as fascinating as I’ve found learning about it! It’s definitely not necessary to have a deep understanding of scientific nomenclature to be able to care for houseplants - but sometimes it’s useful to know which plants are most closely related. It can help you work out where they will grow most happily, or whether a plant you’re considering buying would be similar in care needs to those you already have. At the very least, knowing the scientific name of your plant will make it easier to find out about it - for example, ‘Prayer Plant’ can refer to any plant in the Marantaceaefamily, but if you know whether you have a Maranta, Goeppertia or Ctenanthe, you’ll be able to find much more specific information (pun very much intended).

And whether you love the Latin names or feel like it’s still all Greek to you , at least now you know what it’s doing on the label of your favourite plants.

For up-to-date plant classifications, I have referred, as ever, to the Plant List on World Flora Online, and Kew Gardens’ Plants of the World Online. Both provide links to papers, especially handy for those older classifications, such as the Monstera dubia paper with illustrations in Das Pflanzenreich. I also accessed the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants for detailed information on naming conventions. My familiar standby for the meanings of plant names is Stearn’s Dictionary of Plant Names (William T. Stearn, 1996).